Benjamin’s Stash

These damn talkies will ruin everything!

Cast of Characters:

George Valentin – Jean Dujardin

Peppy Miller – Berenice Bejo

Clifton – James Cromwell

Doris Valentin – Penelope Ann Miller

The Butler – Malcolm McDowell

Constance – Missi Pyle

Peppy’s Maid – Beth Grant

Peppy’s Butler – Ed Lauter

Policeman Fire – Joel Murray

Pawnbroker – Ken Davitian

Al Zimmer – John Goodman

Director – Michel Hazanavicius

Writer – Michel Hazanavicius

Producer – Thomas Langmann

Distributor – The Weinstein Company

Running Time – 100 minutes

Rated PG-13 for a disturbing image and a crude gesture.

George Valentin (Jean Dujardin) is Hollywood’s hottest silent film star of the ’20s. He’s adored by both the public and his gruff boss, Kinograph Studios head Al Zimmer (John Goodman), and has garnered a string of successful pictures to his name.

During the debut screening of his new film, Valentin bumps into Peppy Miller (Berenice Bejo), a natural in front of the camera who he takes under his wing. Their chemistry together wins over both Zimmer and the public; however, as Peppy’s star continues to grow, George’s begins to fade, especially with the arrival of the “talkies” – a new film technology he dismisses as nothing but a fad. However, as that “fad” keeps growing in popularity, he starts to realize that the sun may finally be setting on his famed career sooner than he’d like.

Some films are a sure thing for a studio – comic book films, anything with Star Wars in the title, and for some inexplicable reason, Happy Madison films. Then there are certain pictures that take a little bit of extra effort to convince the studio heads that going all-in is in their best interests – The Passion of the Christ, a film spoken entirely in two dead languages (Latin and Aramaic); 2015’s The Tribe, a film with no spoken or subtitled dialogue and told solely through sign language; and The Artist, a silent film whose story is told primarily through intertitles and the musical score.

Back in the ’20s, the silent film was king, but all that was about to change in 1927 when the first talkie arrived. Some, like The Artist’s main character George Valentin, saw it as a fad that would soon pass, but over the next five years, a San Andreas-sized seismic shift would alter the course of Hollywood forever. In 1929, the year of the first Academy Awards ceremony, all six Best Picture nominees were silent films. Come the next year, four of the five nominees were talkies.

So much for it being just a fad.

In a day and age where movies are bigger, faster and more hyped than ever before, it’d be easy to dismiss The Artist as just a showy, artsy-fartsy gimmick. With the silent film having gone the way of the dinosaur and black-and-white pictures being nowhere as prevalent as they once were, one could easily find themselves distracted by the film’s silent conceit, focusing entirely on the fact they’re watching a silent film to the point it overwhelms the story, characters, and both the technical details and artistry of the picture. Thankfully, such awareness is perfectly appropriate for this movie as it too is every bit as aware as you are that it’s a silent film, and it embraces that awareness with great joy and affection.

French writer/director Michel Hazanavicius isn’t just content to patch together a conventionally filmed biopic of the silent era. Why take the easy route when he can make his film about the silent era a silent film itself? Yes, you can roll your eyes and say the conceit is just a gimmick, and, to be honest, you wouldn’t necessarily be wrong in thinking that. What makes this gimmick work so perfectly, though, is that it’s very crucial to the story, with the film’s novelty being kept sustained by Hazanavicius’s impeccable attention to detail. The Oscar-winning filmmaker goes to great lengths in recapturing the look, sound and tone of the silent era – the 1.33:1 screen ratio, the black-and-white presentation (though presented in black-and-white, cinematographer Guillaume Schiffman did shoot the film in color), shooting at a slightly lower frame rate of 22 fps (standard rate is 24 fps) to recreate the sped-up look of the ’20s silent films, and the musical score serving as the film’s voice. It’s all first-rate craftsmanship of the highest order, and is just a part of what makes The Artist such a captivating watch.

Though Hazanavicius’s efforts can’t be overstated, The Artist provides more than just remarkable technical expertise, as its story delivers a poingnancy that is every bit as remarkable as the film’s presentation. Underneath all the sweeping, pantomimed gestures and melodrama fully on display, there’s a heart at the film’s core that is more than capable of resonating with viewers of all stripes, regardless of if you’re a cinema buff who loves the silent era or a contemporary film fan. We not only care about the characters, but as shown over the course of the film’s passage of time, are also invested in Hollywood’s major shift with the advent of the talkies, as well as the public’s fickle tastes in stardom because of what it potentially means for said characters.

When it comes to the use of music in film, it’s a bit unfortunate how often we tend to overlook a score’s effect on it. Not that they’re dismissed entirely by any means, but they’re understandably appreciated more as a supplement to the overall film. The same can’t be said for this film’s score, which is tasked with carrying a heavier weight than most film scores are required to do in that it’s mostly serving as The Artist’s only sound (I say mostly due to a clever use of sound by Hazanavicius during a key mid-point sequence that works quite effectively). It’s more than just the background music; in this case, as Aerosmith once said, the music is literally doing the talking. The spirit of the story, all of the emotions, the tone, the essence of each character – every aspect of the film hinges on Ludovic Bource’s excellent, Oscar-winning work. One false note could quickly alter the interpretation of the film, yet Bource strikes all the right notes needed to give The Artist its incredible voice.

Casting plays a vital role in aiding the film’s authenticity, and both Hazanavicius and casting director Heidi Levitt assemble a pitch-perfect cast that looks like it could’ve been plucked straight from the film’s period. The supporting cast features small but pivotal appearances from veteran players such as John Goodman, James Cromwell, Malcolm McDowell and Penelope Ann Miller, all of whom are terrific. Goodman is a wonderfully inspired choice to play the gruff, cigar-chomping studio head; James Cromwell turns in a very touching performance as George’s trusty chauffeur Clifton; and Miller delivers a short but memorable performance as George’s long-suffering wife (who scores a nice laugh-out-loud jab by way of a single note she leaves behind for her husband).

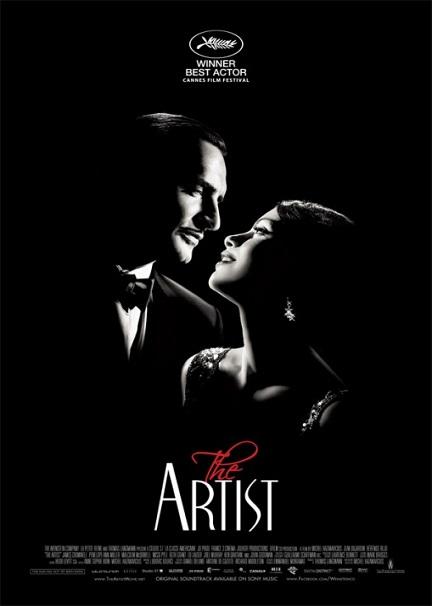

More so than the supporting cast, the casting of the two leads is a make or break for this film, and The Artist finds the perfect fits in Jean Dujardin and Berenice Bejo, both of whom have worked previously with Hazanavicius on the director’s OSS 117 spy parody franchise. Simply put, Dujardin and Bejo are magnificent here, with the former going on to win Best Actor at the 2012 Oscars (Bejo would also receive a nomination for Best Supporting Actress). Carrying himself with a suave, debonair swagger that recalls silent film legend Douglas Fairbanks, Dujardin brings charm, humor and even heartbreak to the once larger-than-life star George Valentin, effortlessly maneuvering through each emotional turn without skipping a single beat. As Peppy Miller, the lovely Berenice Bejo lives up to her character’s name with a scene-stealing performance that is pure spark, while still showcasing superb emotional range in a few scenes between her and Dujardin that are deeply affecting.

The music is certainly the film’s voice, but no question, Dujardin and Bejo are the film’s heart.

An affectionate love letter to the silent era that also works as a great silent film itself, The Artist comes to wondrously expressive life thanks to Jean Dujardin and Berenice Bejo’s tremendous peformances and Michel Hazanavicius’s combined sharp eye for technical detail and strong adoration of the history of cinema. Sure, maybe it’s supported by what many see as a gimmick, but The Artist takes that gimmick and transforms it into something truly beautiful.

Stash Tier: Diamond Stash